Modern Investment Strategies: A Comprehensive Dive into Technical and Market Subjects

In the ever-evolving world of finance, investment strategies have undergone significant transformations. With the rise of technology, globalization, and a more interconnected world, modern investment strategies have become more sophisticated, blending both technical and market-based approaches. This article aims to provide a comprehensive introduction to these strategies, offering insights into their nuances and how they fit into today’s financial landscape.

The Evolution of Investment Strategies

Historically, investment strategies were straightforward, often based on simple buy-and-hold philosophies or basic fundamental analysis. However, as markets became more complex and information more accessible, the need for advanced strategies grew.

Table 1: Evolution of Investment Strategies Over Time

| Era | Dominant Strategy | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1980s | Buy and Hold | Long-term, minimal trading |

| 1980s-2000s | Fundamental Analysis | Based on company financials, industry trends |

| 2000s-Present | Technical Analysis | Uses price patterns, trading volumes |

Technical vs. Market-Based Strategies

Technical Strategies: These are based on the belief that historical trading activity, including price changes and trading volume, can forecast future price movements. Key tools include:

- Chart Patterns: Recognizing patterns like ‘head and shoulders’ or ‘double tops’.

- Indicators & Oscillators: Tools like Moving Averages or the Relative Strength Index (RSI).

Market-Based Strategies: These focus on broader market indicators, economic data, and other macro-level factors. Examples include:

- Momentum Investing: Capitalizing on current market trends.

- Value Investing: Identifying undervalued assets based on intrinsic value.

Comparison Table: Technical vs. Market-Based Strategies

| Criteria | Technical Strategies | Market-Based Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Historical Data | Intrinsic Value |

| Key Tools | Charts, Oscillators | Economic Data, Trends |

| Time Horizon | Short to Medium | Medium to Long |

| Risk Profile | High | Moderate |

Modern Investment Tools & Platforms

With advancements in technology, a plethora of tools and platforms have emerged, aiding investors in implementing modern strategies. These range from AI-driven robo-advisors to advanced trading platforms offering real-time analytics.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) have revolutionized investment strategies. Algorithms can now predict market movements, identify investment opportunities, and even automate trading activities. However, while they offer efficiency, they also bring challenges, especially when it comes to transparency and understanding the decision-making process.

Navigating Modern Investment Strategies

For investors, understanding and navigating these modern strategies requires continuous learning. It’s essential to:

- Stay updated with market trends and technological advancements.

- Understand the risks associated with each strategy.

- Diversify investments to spread and mitigate potential risks.

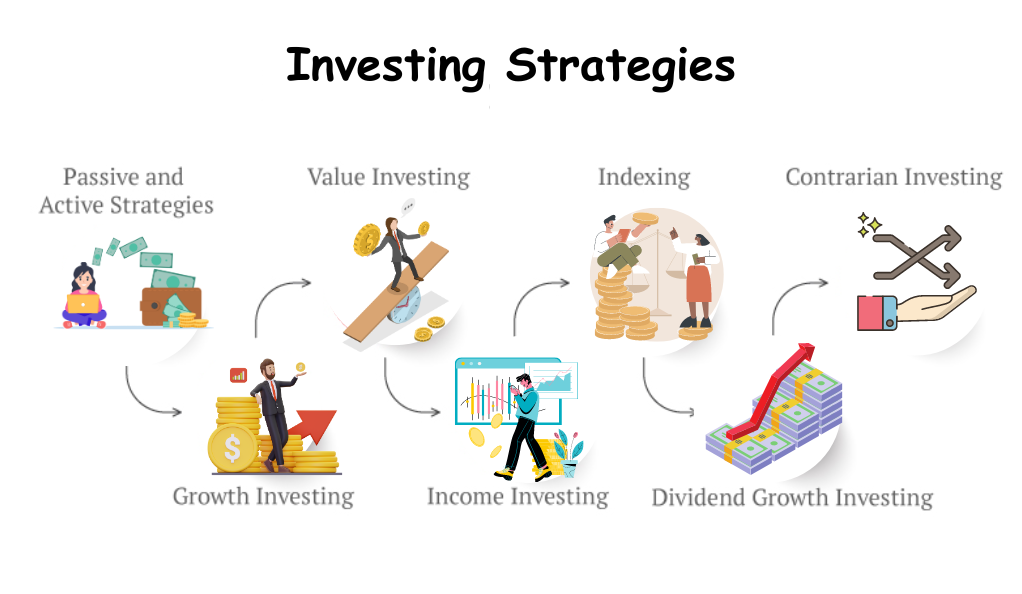

Investing Strategies for the Modern Age

The Power of Compound Interest

Often referred to as the ‘eighth wonder of the world’ by financial enthusiasts, compound interest is the mechanism where interest is calculated on the initial principal, which also includes all of the accumulated interest from previous periods on a deposit or loan.

Understanding Compound Interest

At its core, compound interest means earning interest on interest. It allows investments to grow exponentially over time.

The Rule of 72

A quick way to estimate how long it will take for an investment to double at a fixed annual rate of interest. Divide 72 by your annual interest rate, and the result is the approximate number of years it will take for your investment to double.

The Long-Term Impact

Even with modest interest rates, the effects of compounding can be significant over long periods. For instance, a $10,000 investment at a 5% annual return will grow to over $40,000 in 25 years, primarily due to compound interest.

Balancing Long-Term and Short-Term Goals

Every investor has a unique financial journey, characterized by individual goals, risk tolerance, and time horizons.

Short-Term Goals

These are objectives one hopes to achieve within the next 1-3 years. They might include saving for a vacation, building an emergency fund, or purchasing a car. Investments for these goals are typically more conservative to preserve capital.

Long-Term Goals

These span over several years or even decades and might include retirement planning, buying a home, or funding a child’s education. Given the extended time horizon, investors can afford to take on slightly more risk in hopes of higher returns.

Striking a Balance

It’s crucial to allocate assets in a manner that reflects both immediate needs and future aspirations. Diversifying investments across various assets can help achieve this balance, ensuring that short-term market volatility doesn’t derail long-term objectives.

The Role of a Wealth Advisor in Today’s Financial Climate

In an age of information overload, the guidance of a seasoned wealth advisor has never been more valuable.

Personalized Financial Planning

Every individual’s financial situation and goals are unique. A wealth advisor crafts tailored strategies that align with an individual’s specific needs and aspirations.

Staying Abreast of Market Trends

The financial market is dynamic, with factors like geopolitical events, technological advancements, and economic indicators influencing its direction. Wealth advisors keep a pulse on these shifts, advising clients on potential opportunities or threats.

Risk Management

One of the primary roles of a wealth advisor is to help clients understand and manage investment risks. They ensure that the client’s portfolio is diversified and aligned with their risk tolerance.

Estate Planning and Retirement

Beyond just investments, wealth advisors assist in estate planning, tax strategies, and ensuring a smooth transition to retirement.

Value Investing: The Art of Bargain Hunting

The Essence of Value Investing

Value investing is predicated on the belief that the stock market occasionally undervalues companies. This undervaluation can be due to various reasons, including short-term business challenges, market overreactions, or macroeconomic factors.

Intrinsic Value vs. Market Price

At the heart of value investing lies the differentiation between a company’s intrinsic value and its current market price. The intrinsic value is an estimate of what a company is genuinely worth, taking into account all tangible and intangible factors. When the market price of a stock is below its intrinsic value, it presents a potential buying opportunity for value investors.

Margin of Safety

Another cornerstone of value investing is the concept of the “margin of safety.” This refers to the difference between a stock’s intrinsic value and its market price. A larger margin offers a cushion against potential losses, making the investment less risky.

Understanding Undervalued Assets

Identifying undervalued assets is both an art and a science. It requires a deep dive into a company’s financials, understanding its business model, and assessing its competitive landscape.

Financial Analysis

This involves scrutinizing a company’s balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement. Healthy cash reserves, low debt levels, and consistent profitability are positive indicators.

Qualitative Factors

Beyond just numbers, it’s essential to understand the company’s management quality, its position within the industry, and any competitive moats that might protect its future earnings.

Macroeconomic Considerations

External factors, such as economic downturns, regulatory changes, or geopolitical events, can also lead to assets being undervalued. Value investors remain vigilant of these broader trends to identify potential investment opportunities.

The Role of the Price-Earnings Ratio (P/E)

The P/E ratio is one of the most widely used tools in the arsenal of a value investor. It provides a snapshot of how much investors are willing to pay for a company’s earnings.

Calculating P/E

The P/E ratio is calculated by dividing a company’s current stock price by its earnings per share (EPS). A lower P/E ratio can indicate that a stock is undervalued, while a higher P/E might suggest overvaluation.

Comparative Analysis

The P/E ratio is most effective when used comparatively. Investors often compare a company’s P/E to that of its peers, its historical P/E, or the average P/E of the broader market.

Limitations of P/E

While the P/E ratio is a valuable tool, it’s not infallible. It doesn’t account for growth potential, and a low P/E might sometimes be indicative of underlying business challenges. Hence, it’s crucial to use the P/E ratio in conjunction with other valuation metrics and qualitative analysis.

Growth Investing: Capitalizing on Rapid Expansion

The Philosophy Behind Growth Investing

Growth investing is rooted in optimism. Investors adopting this strategy are primarily concerned with the future potential of a company, often overlooking traditional valuation metrics.

- Forward-Looking: Unlike value investors, who focus on present valuations, growth investors are more concerned with future potential. They’re willing to pay a premium today for anticipated future earnings.

- Risk and Reward: Growth investing can be riskier than other strategies. The anticipation of higher returns comes with the acceptance of higher volatility and potential for significant losses.

Characteristics of Growth Assets

Growth assets, typically, are those of companies in the expansion phase of their lifecycle. They exhibit certain distinct characteristics:

High Revenue Growth

One of the most evident signs of a growth asset is consistently high revenue growth, often significantly above industry averages.

Reinvestment

Growth companies often reinvest a substantial portion of their profits back into the business, fueling further expansion. This reinvestment can be in research & development, expanding into new markets, or enhancing infrastructure.

Competitive Advantage

Whether it’s a unique technology, a strong brand, or a dominant market position, growth companies often have a distinct edge that allows them to outperform competitors.

Sector Trends

Growth assets often belong to industries that are currently in vogue. Whether it’s tech during the dot-com boom or renewable energy in more recent times, these sectors attract significant investor interest due to their future potential.

Balancing Price Appreciation and Dividends

For growth investors, the primary source of returns is price appreciation. However, dividends, or the lack thereof, play a crucial role in this investment strategy.

Price Appreciation

As companies grow and their revenues increase, their stock prices typically rise, leading to capital gains for investors. This price appreciation is the primary allure of growth investing.

Dividends

Growth companies, given their focus on reinvestment, often do not pay dividends. Instead of distributing profits to shareholders, they channel these funds back into the business. For investors, this means the absence of a steady income stream, making capital gains even more critical.

The Trade-off

While the lack of dividends might deter some investors, those aligned with the growth investing philosophy view it positively. They believe that the company’s reinvestment strategies will lead to even greater price appreciation in the future, compensating for the absence of dividend income.

Momentum Investing: Riding the Wave

Momentum investing is akin to surfing: it’s all about catching the right wave and riding it to its peak. In the financial world, this strategy involves buying stocks that have shown an upward trend in recent times, with the expectation that the trend will continue. This article delves deep into the essence of momentum investing, exploring the underlying concept of recent performance predicting future trends and the inherent risks associated with this approach.

The Underpinnings of Momentum Investing

At its core, momentum investing is a testament to the adage “the trend is your friend.” It’s a strategy that capitalizes on existing market trends, irrespective of the underlying fundamentals of the stocks in question.

Behavioral Economics

Momentum investing finds its roots in behavioral economics. It operates on the premise that stock prices do not always reflect their true value immediately. Instead, they adjust over time, creating momentum that astute investors can exploit.

Short-Term Focus

Unlike value or growth investing, which might look at long-term potential, momentum investing is inherently short-term. Investors are looking for stocks that have performed well in the recent past, typically over periods ranging from a few months to a year.

Recent Performance as a Predictor

The central tenet of momentum investing is that recent performance can be a reliable indicator of near-future performance.

- Historical Analysis: Numerous studies have shown that stocks showing strong performance over a 3- to 12-month period tend to continue outperforming the market in the subsequent period.

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: As more investors notice a stock’s upward trajectory and buy into it, the demand (and consequently, the price) continues to rise, further fueling the momentum.

- Market Anomalies: While efficient market hypothesis suggests that all available information is already priced into stocks, momentum investing capitalizes on market anomalies where information is not immediately reflected in stock prices.

The Risks of Riding the Wave

Like all investment strategies, momentum investing is not without its risks.

Reversals

Just as stocks can exhibit upward momentum, they can also experience sharp reversals. If investors are late to recognize this change in trend, it can lead to significant losses.

Volatility

Momentum stocks, given their reliance on short-term trends, are often more volatile than their counterparts. This volatility can lead to rapid gains, but also steep declines.

Overvaluation

As more and more investors jump onto a momentum stock, there’s a risk of the stock becoming overvalued, detaching from its intrinsic value. When the market corrects this overvaluation, momentum investors can face substantial losses.

External Factors

Momentum investing is susceptible to broader market dynamics. Macroeconomic changes, geopolitical events, or industry-wide disruptions can halt momentum, leading to rapid shifts in stock trajectories.

Dollar-Cost Averaging: Mitigating Market Volatility

In the unpredictable world of investing, where market fluctuations are a given, dollar-cost averaging (DCA) emerges as a beacon of stability. This strategy, rather than attempting to time the market, emphasizes regularity and discipline. This article delves into the core principle of dollar-cost averaging, its benefits, and the potential drawbacks investors should be aware of.

The Principle of Consistent Investment Amounts

Dollar-cost averaging is built on a simple yet powerful concept: investing a fixed amount of money at regular intervals, regardless of market conditions.

Consistency Over Timing

Instead of trying to predict the best times to buy or sell, DCA investors allocate a set amount of money at predetermined intervals, such as monthly or quarterly.

Automatic Purchases

Many investors automate their DCA investments, ensuring they stick to the strategy without being swayed by emotions or market news.

Market Fluctuations

As the market ebbs and flows, the consistent investment amount will buy more shares when prices are low and fewer shares when prices are high. Over time, this can result in a lower average cost per share.

Benefits of Dollar-Cost Averaging

DCA offers several advantages that make it appealing to both novice and seasoned investors:

- Mitigating Risk: By spreading out investments over time, DCA reduces the risk of investing a large amount at an inopportune moment.

- Emotional Detachment: Regular, automated investments help investors avoid emotional decision-making, which can often lead to buying high and selling low.

- Simplicity: DCA is straightforward to understand and implement, making it accessible even to those new to investing.

- Flexibility: Investors can start with a small amount and adjust their contributions as their financial situation changes.

Drawbacks of Dollar-Cost Averaging

While DCA offers numerous benefits, it’s essential to be aware of its limitations:

- Missed Opportunities: If the market is on a prolonged upward trajectory, DCA investors might miss out on some gains by not investing a lump sum at the outset.

- No Guarantee of Profit: While DCA can lower the average cost of investments, it doesn’t guarantee a profit. If the market experiences a prolonged downturn, investors can still face losses.

- Overemphasis on Regularity: In some cases, being too rigid with DCA can prevent investors from taking advantage of significant market dips outside their regular investment schedule.

Buy and Hold Strategy: The Long-Term Approach

The Core of Buy and Hold

The buy and hold strategy is rooted in the belief that, in the long run, well-chosen investments will yield positive returns, despite short-term market volatility.

- Long-Term Vision: This strategy requires investors to look beyond temporary market downturns and focus on the long-term potential of their investments.

- Reduced Transaction Costs: By holding onto investments for extended periods, investors can significantly reduce transaction costs associated with frequent buying and selling.

- Compounding Returns: The buy and hold approach allows investors to capitalize on the power of compounding, as reinvested dividends and interest can generate additional earnings over time.

Warren Buffett’s Endorsement

Warren Buffett, the Oracle of Omaha, is perhaps the most famous proponent of the buy and hold strategy.

- Value Over Price: Buffett often emphasizes the distinction between a stock’s price and its value. While prices may fluctuate, a company with strong fundamentals will, in his view, always present long-term value.

- Historical Success: Buffett’s investment in companies like Coca-Cola and Apple, which he has held for decades, showcases the success of this strategy. His ability to identify companies with enduring value has made him one of the world’s most successful investors.

- Patience and Discipline: Buffett’s approach underscores the importance of patience and discipline, often advising investors to buy stocks they would be comfortable holding even if the market closed for ten years.

Stock Picking vs. Passive Investment

The buy and hold strategy often leads to a debate between active stock picking and passive investment.

Active Stock Picking

This involves selecting individual stocks based on research and analysis. Proponents believe that with careful analysis, it’s possible to identify undervalued stocks with high growth potential.

Passive Investment

This approach involves investing in broad market indices through vehicles like index funds or ETFs. Passive investors believe that it’s challenging to consistently outperform the market through stock picking, and thus, it’s better to mirror the market’s performance.

The Debate

While Buffett is known for his stock-picking prowess, he has often recommended passive index funds for the average investor, citing their lower fees and consistent returns. The debate between these two approaches continues, with each having its merits and drawbacks.

Diversification: Spreading the Risk

The Rationale Behind Diversification

Diversification is a risk management strategy that mixes a variety of investments within a portfolio.

- Risk Mitigation: The rationale is that different assets will, on average, yield higher returns and pose a lower risk than any individual investment found within the portfolio.

- Unpredictable Markets: Given the unpredictable nature of markets, diversification ensures that even if one or more investments perform poorly, others might perform well, balancing out the overall performance.

- Achieving Consistent Returns: While diversification doesn’t guarantee against a loss, it aims at achieving consistent returns by spreading investments across various assets.

Investing Across Multiple Asset Classes

A truly diversified portfolio spans across multiple asset classes, ensuring a balanced approach.

- Equities: Investing in stocks offers potential for high returns, but they come with higher volatility.

- Fixed Income: Bonds and other fixed-income securities provide regular interest income and are generally less volatile than stocks.

- Real Estate: Real estate investments can offer both rental income and capital appreciation.

- Commodities: Assets like gold, oil, and agricultural products can act as a hedge against inflation and economic downturns.

- Alternative Investments: This category includes assets like hedge funds, private equity, and collectibles, offering diversification beyond traditional asset classes.

The S&P 500 – A Diversification Benchmark

The S&P 500, comprising 500 of the largest publicly traded companies in the U.S., serves as a prime example of diversification.

Broad Representation

The index represents various sectors, from technology and healthcare to finance and consumer goods, providing a comprehensive view of the U.S. economy.

Risk and Return

While investing solely in the S&P 500 doesn’t offer diversification across different asset classes, it does spread the risk across multiple sectors and companies. Historically, the S&P 500 has provided consistent long-term returns, albeit with periods of volatility.

Passive Investing

Many investors choose to invest in S&P 500 index funds as a form of passive investment, capitalizing on the diversification benefits of the index without the need for active stock picking.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT): A Scientific Approach

The History and Development of MPT

The roots of Modern Portfolio Theory can be traced back to the work of Harry Markowitz in the early 1950s.

Origins

In his seminal 1952 paper, “Portfolio Selection,” published in the Journal of Finance, Markowitz introduced the concept of evaluating investments based on both risk and return.

Efficient Frontier

Markowitz’s work led to the concept of the ‘efficient frontier’ – a curve representing the set of portfolios that maximize expected return for a given level of risk.

Nobel Recognition

For his pioneering work in this field, Markowitz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990, cementing MPT’s importance in financial theory.

Benefits of Modern Portfolio Theory

MPT, with its scientific approach to portfolio construction, offers several advantages:

- Risk-Return Optimization: MPT allows investors to construct a portfolio that offers the highest possible return for a given level of risk.

- Diversification: Central to MPT is the idea of diversification. By combining assets that are not perfectly correlated, investors can achieve a more favorable risk-return profile.

- Quantitative Foundation: MPT provides a mathematical framework for portfolio construction, moving away from subjective decision-making.

- Asset Allocation: MPT emphasizes the importance of asset allocation over individual security selection in determining portfolio performance.

Criticisms of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

Modern Portfolio Theory, or MPT, has been a foundational concept in finance and investment for decades. Developed by Harry Markowitz in the 1950s, it introduced the idea of optimizing portfolios based on expected returns and volatility. However, as with any theory, MPT has faced its share of criticisms over the years:

Reliance on Historical Data

One of the primary criticisms of MPT is its heavy dependence on historical data to predict future returns. Detractors argue that past performance isn’t always indicative of future results. The financial markets are influenced by a myriad of ever-changing factors, and what happened in the past might not necessarily repeat in the future.

Assumption of Investor Rationality

MPT operates on the premise that all investors are rational beings who make decisions purely based on risk and expected returns. However, numerous studies in behavioral finance have shown that emotions, biases, and other psychological factors often play a significant role in investment decisions, challenging the very foundation of MPT.

Over-Reliance on Quantitative Models

The mathematical models underpinning MPT are both its strength and its weakness. While they provide a structured approach to portfolio optimization, they can sometimes oversimplify the complexities of the real world. Critics argue that an over-reliance on these models can lead to blind spots, especially when unforeseen market events occur.

Market Anomalies and Inefficiencies

MPT assumes that markets are efficient, meaning all available information is already reflected in asset prices. However, there have been numerous instances of market anomalies, where asset prices deviate from their intrinsic values. These anomalies, which can be caused by factors like investor sentiment, misinformation, or herd behavior, challenge the idea that markets always behave rationally and efficiently.

Conclusion

In the ever-evolving landscape of finance, modern investment strategies stand as testament to the blend of innovation, technology, and market insights. As we’ve journeyed through the intricacies of technical and market subjects, it’s evident that successful investing today requires a harmonious balance of data-driven analytics and a deep understanding of market dynamics. Whether one leans towards the mathematical precision of technical analysis or the broader perspectives of market subjects, the key lies in continuous learning and adaptability. As the world of investment continues to transform, these strategies will undoubtedly serve as guiding lights, illuminating the path for investors navigating the complex waters of the financial world.

Bitcoin-up is dedicated to providing fair and trustworthy information on topics such as cryptocurrency, finance, trading, and stocks. It's important to note that we do not have the capacity to provide financial advice, and we strongly encourage users to engage in their own thorough research.

Read More